ADWOA’S FRIENDS ARE NOT REAL

INTRODUCTION TO STORY

An architecture of imagined companionship, it is deeply anchored in the surrealist atmosphere of Jack Stauber’s animation classic Opal. The plot unfolds within the walls of a house characterized by distorted figures which feel strangely familiar, yet are equally petrifying. It unveils the hidden trauma of loneliness, of residing in an environment that appears wholesome, yet suffers a piercing deficit of love. Imagination in Opal captures protection and confinement, a soothing escapism but also a prison. That fragile emotion is reflected by this project, where the silence of rejection sets the stage for Adwoa’s universe.

Adwoa is a girl child who has been abandoned. The work does not provide an exhaustive explanation for this situation. This silence is deliberate. What we experience, however, is a child gliding through a universe which is damn quiet. Her laughter is echoed by the empty lofty walls. Her questions evaporate into still air. She plays without partners, dines without a soul across the table, and speaks to objects which refuse to respond.

Her bonds are severed, yet she remains resilient. She establishes rapport in the only way she can. Her companions are neither peer nor super heroes. They are dolls.

These dolls become central to her survival and sense of being. They are clothed, nourished and spoken to like humans. They do not interact, but their presence fills the void within Adwoa, and is enough hope for her to hold unto. Each image captures a ritual of care which is both compassionate and heartbreaking.

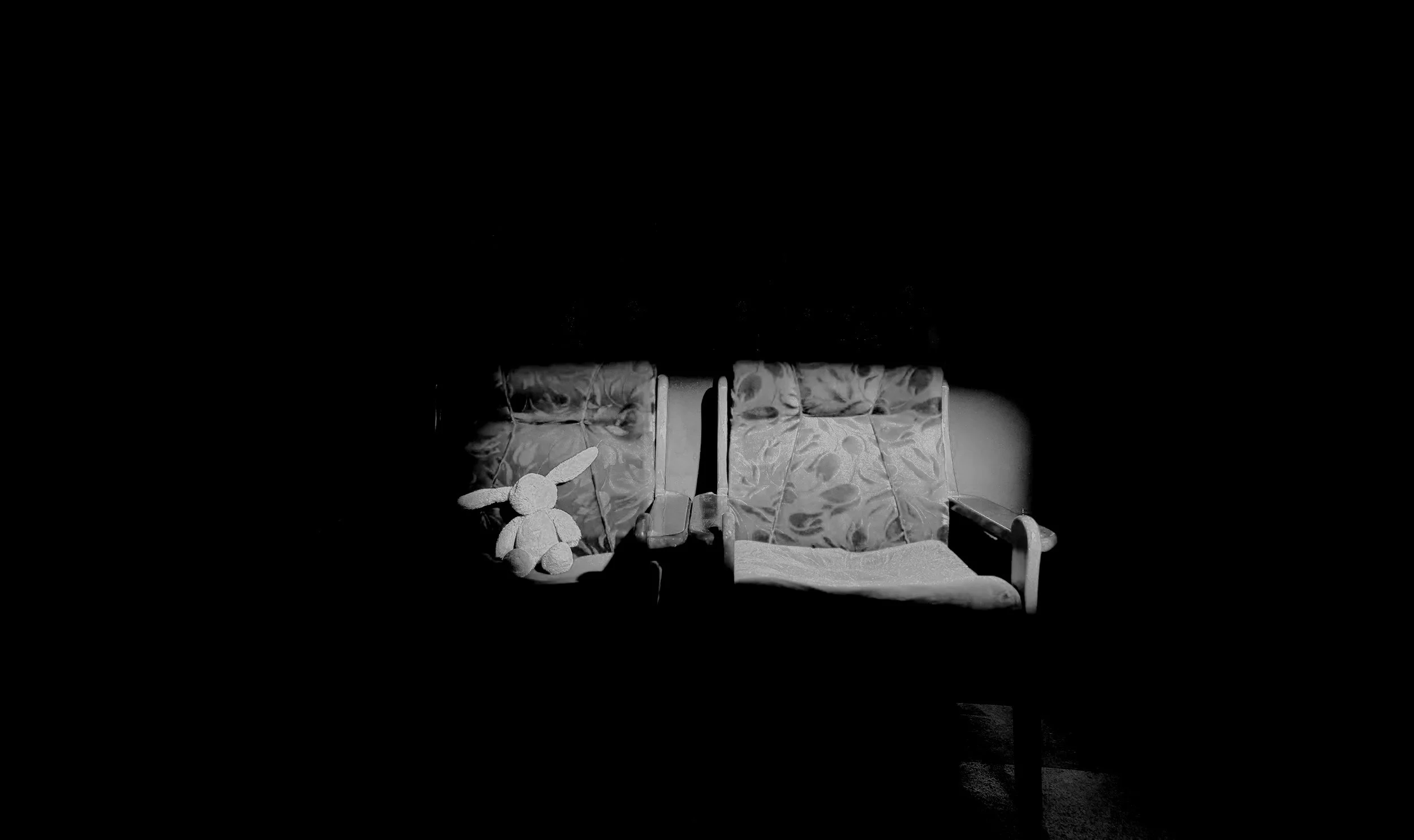

A colourful tea party is curated for eccentric attendees who cannot sip. At bedtime, Adwoa tucks her dolls beneath their makeshift duvet, an experience she herself yearns for, yet is denied. She whispers, and although it is a one-way conversation, she simply does not give up. Adwoa continues to express herself. In those gestures, the resilience of a child is laid bare. To Adwoa, they are alive, they are not just material objects. They exist in a conflicted universe between emptiness and happiness.

This project is not about Adwoa alone. It is also about the role of the audience. Each image leaves gaps that deny closure. Sparse rooms, dim corners, and unanswered gestures resist plain storytelling. Where is her family? Why is she left alone? When did this begin and how long has it stretched?

These questions are triggered without meaningful answers, mirroring the psyche of depression itself. Depression is rarely explained. It is a library of unpublished memoirs, an absence that remains unfilled. The photographs become mirrors which question the audience, to reminisce and recall their own stories of memories and loss.

At its core, Adwoa’s Friends Are Not Real is about the shared condition of rejection. We are all Adwoa through moments of our finite lives. While some struggle with the pain of confidants who suddenly disappeared, others shoulder the weight of loved ones that did not love in the ways they were meant to. Many have killed parts of themselves in order to become someone else. Adwoa’s solitude is unique, but it gestures toward the universal. It is an elegy for the countless invisible moments of rejection which shapes human lives.

What embodies the power of this work is its restraint. The loneliness here is not a spectacle. It is a quiet fact. It resides in little gestures: a child filling up cups with imaginary tea, staring into a wall, or pressing a doll against her arm as if cotton could hold the night at bay.

The dolls, with their glass eyes and poker faces, do not disguise their myth. They declare it. They sit as a stark reminder of what should have been there and a replacement for what is not.

Yet within this absence there is also fortitude. Adwoa does not stop reaching out. She continues to care for the dolls, to develop tiny rituals of companionship, to invest emotions into people who would not return it. This is not delusion. It is resilience. It is the stubborn insistence that connection matters, even when it must be invented. The project does not end in despair but in persistence. It shows how, even in silence, the human heart keeps searching for warmth.

The Exhaustion

The photograph arrests us first with its stillness. Adwoa sits in a chair, her head bowed, her body folded in on itself, her shoes slipped from her feet and lying unattended on the floor. The room seems bare, except for her, a stuffed toy seated beside her, and the light that frames her in a square of illumination. Yet what the image truly holds is not its objects, but its silences, its absences, its weight of weariness that is almost palpable.

Adwoa’s posture tells the story: she is tired, but not with the tiredness of a body at the end of a long day. Hers is the exhaustion that comes from repetition, from being caught in a cycle that offers no release. She is a child, but her bowed head carries the heaviness of someone who has had to carry too much. This photograph names that weight. It names it not as play, not as innocence, but as exhaustion.

Look behind her. On the wall, the light gathers into shapes that resemble the silhouettes of two adults, a mother, a father, or perhaps simply two figures who should have been parents. Their forms are spectral, projected rather than embodied, shadows rather than flesh. They are there, and yet not there. Their presence is nothing more than an absence given shape. Adwoa sits before these ghostly guardians, a child framed against the echo of a family that exists only in suggestion. She is in dialogue with the possibility of care, but never its reality.

This, too, is where the exhaustion lies. It is the weariness of a child who sees what should have been, who senses the outline of care but never feels its substance. Her companions, then, must be self-made. To her left, the darkness thickens into a form that seems to intrude on the room’s light. This figure belongs not to the world of adults, but to the world of imagination. It is one of the friends she has conjured into being, companions who come alive to shield her from the solitude she has inherited. They call to her, urging her into play, but even play has become its own burden.

To enter their world, she must abandon her own reality, and each act of escape exacts a toll. The friends may soothe, but they also remind her that they are illusions. They are the scaffolding of a survival she should never have had to construct. Each return to them is both a relief and a wound, a gesture of defiance against neglect but also a mirror reflecting it back. No wonder she sits now in stillness, drained by the effort. Escapism has become its own trap, and she is caught in its loop.

The toy beside her embodies this paradox. A stuffed creature, soft and harmless, meant to be a child’s companion. But placed here, on the chair that should have held a parent, it is no longer just a toy. It becomes the placeholder of presence, a quiet indictment of absence. It sits where love should have sat. Its silence is deafening.

The light that falls on Adwoa is merciless. It frames her, isolates her, traps her. It is at once a kind of grace, without it, she would be lost in shadow and a kind of prison, exposing her solitude with unrelenting clarity. The beam becomes a cage of visibility. It illuminates her but offers no comfort, no hand, no escape. The exhaustion it reveals is not only hers but ours, the exhaustion of witnessing what we would rather not see: the child alone, the parent absent, the imagination bent into survival.

And yet, even here, there is poetry. The photograph does not sensationalize her fatigue. It does not dramatize her loss. It simply allows the truth to rest in her posture, in the cast of the shadows, in the faint scatter of objects left behind. It compels us to see how imagination, that most radiant of childhood faculties, can be both a sanctuary and a burden. It forces us to reckon with the paradox of escapism: that the very act which preserves us can also deplete us.

Adwoa becomes, in this image, more than herself. She is the embodiment of exhaustion as an existential condition the exhaustion of carrying absence, of conjuring companions, of looping endlessly between neglect and survival. She is the face of a solitude that refuses to be softened. She is the tired child and the abandoned child, but she is also the truth-teller, showing us how absence can take form, how imagination can collapse under its own weight, how survival is not always triumph but sometimes only endurance.

The Exhaustion, then, is not just her exhaustion. It is ours as viewers, as witnesses who cannot pretend we do not see the ghosts on the wall, the toy on the chair, the child bowed under her own imagination. It is the exhaustion of a truth that refuses to be escaped.

The Twirl

Adwoa spins in a deliberate circle, her white dress ascending into a halo that catches the light and glows against the shadows. Her head bends gently, her eyes resting on the space just before her hands. The camera shows nothing there, yet she holds something in her mind. To her, it is a friend, a doll alive and present in the rhythm of her dance. To us, it is empty air. This absence is not a mistake. It is the central tension of the image. The camera documents only the visible, but Adwoa dwells in the universe of the unseen. The photograph forces the question of what counts as real: is it only what the eye can capture, or what the heart insists upon?

The room around her is modest. It contains a cabinet lined with frames and carved figures, silent witnesses to her abundant and lonely hours. They sit quietly in the background, each one a relic that watches but does not intervene. The stage is hers alone.

The light falls in a narrow column, making her the centre of attention, as if she were an actress in a play where the stage and the audience exist only in her imagination. She twirls not for others but for the circus she has created to absorb her solitude. In this performance she is both star and spectator, both player and witness, and this doubling becomes her way of resisting abandonment.

This moment goes beyond a child’s fun. It is a ritual, an act of resilience through motion. The unseen doll is not simply a toy. It is her trusted lieutenant, a vital participant in the choreography. While adults may see a child spinning in a dress, children know that she is not alone. The absence we register as void is for her a companionship too real to doubt.

The black and white palette strips away distraction, leaving only texture, light, and shadow. The absence of the doll becomes more powerful in this stripped frame. It is not missing because it was forgotten. It was never meant to be captured by the lens of a camera. Some forms of companionship leave no physical trace, yet they remain binding, even sacred.

The Twirl is a turning point in Adwoa’s Friends Are Not Real. Here she no longer looks outward for company. The inward relationship between herself and her imagined friends is enough, at least for the time being. And so she twirls, radiant and complete in her own universe, her unseen friend loyally in her harmless arms.

Play Time

Adwoa stretches across the room in her white dress, arms lifted as she raises her doll toward the faint light filtering through patterned curtains. The rest of the room lies in shadow, with only fragments visible, an old fan, a chair, and the stillness that surrounds her movement.

The doll becomes more than a toy. It is a partner, a substitute for companionship, a fragile stand-in for the love she longs for. Her body balances on her toes, showing both the effort of reaching and the yearning to rise above the silence.

The room carries its own weight. Curtains heavy with age, furniture worn, and a fan sitting idle. Yet against this backdrop, Adwoa insists on play. She turns absence into presence. She weaves joy into a space that has none to offer.

Play Time is not about a child holding a doll. It is about persistence in the face of abandonment. It is about the courage to invent companionship when real connection is denied. It shows how play becomes survival, and how survival becomes protest.

The Watchers

Adwoa stands at the center, dressed in white, yet almost absorbed by the darkness that surrounds her. The light does not fully claim her. Instead, it divides her, making her both present and absent, both subject and silhouette. Her face lingers in shadow, as if she is only half allowed to exist, a child suspended between visibility and erasure.

Behind her, framed pictures lean against a blue wall. They are scenes of other people, caught in paint and memory, frozen forever in gesture and form. These images act like stand-ins for family. They watch her but never meet her. They suggest presence but offer no embrace. Their silence is louder than words.

Objects rest at her side, cups and glasses stacked in waiting. They are vessels meant for company, but their emptiness echoes the absence that fills the room. They hold the shape of gatherings that never arrive. Together with the paintings, they become symbols of a life populated with appearances but devoid of care.

This photograph is not about emptiness alone. It is about the strange weight of presence that fails to hold. Adwoa is surrounded by objects and faces, yet she remains untouched by them. They confirm her solitude rather than relieve it. Like the dolls she tends to in other images, these frames and vessels mimic connection while delivering none.

The tension here is quiet but piercing. It shows a child who has been placed in a space of looking and being looked at, but never truly being seen. The watchers are many, but they are lifeless. The company is arranged, but it is void. Adwoa remains caught in the space between being visible to the eye and invisible to the heart.

Silent Company

The image shows Adwoa in a white dress, standing in a dimly lit room where a single harsh beam of light defines her presence against the shadows. She holds a doll close to her chest, not as a toy, but as both comfort and mirror. Her gaze is steady and direct, carrying the stillness of innocence mixed with a maturity forced by solitude.

Around her, the setting feels heavy with memory. The old cabinet and framed pictures hint at a history that presses into the present. The stark contrast of light and darkness sharpens the sense of absence, as if Adwoa exists at the fragile edge between being a child and confronting abandonment. The doll, with its frozen expression, becomes a stand-in for those who are missing, amplifying the fragile companionship she invents for herself.

In keeping with the spirit of Adwoa’s Friends Are Not Real, this image speaks through what is not shown. It draws attention to the silence in the room and to the figures who should be there but are absent. It asks us to consider what kind of company must be created when none is given, and how the human need for connection does not fade, even when it must be imagined.

The Forsaken Toy

In this image, Adwoa stands in a pristine white dress, her posture poised yet burdened with a subtle defiance. Her arms rest firmly on her hips, and her gaze is sharp, as if daring the silence around her to speak. At her feet lies a doll, face down on the floor, its body twisted away from the light. Once it was a symbol of play and affection, an intimate partner in her hours of solitude. Now it is discarded, caught in the shadow of her stance. The act is quiet but decisive, a gesture of abandonment both literal and symbolic.

The room is heavy with memory. The blue walls are adorned with old framed paintings and faded décor, remnants of another time that press themselves insistently into the present. The cabinet behind her holds fragile glassware and domestic relics, yet none of them seem alive. They sit frozen, gathering dust, waiting without purpose, echoing the same stillness that has settled over the girl. The air is thick with a sense of something already broken, something that has lingered too long in silence.

The doll transforms the scene from portrait to metaphor. Its fall is not accidental. It speaks of innocence that has slipped away, of the fragile ways a child copes when imagination and its companions no longer suffice. The contrast between Adwoa’s upright posture and the doll’s collapse reveals the painful crossing from dependence to resilience. She is too young to carry such a gaze, too young to abandon what once gave her comfort. Yet the image insists that she has already stepped into that space, a child forced to learn the hardness of detachment before she is ready.

The light isolates her, setting her apart from the muted world of objects and shadows that surrounds her. Her presence is fierce, unyielding, even as the doll beneath her remains inert, a reminder of what has been cast aside. In this balance of vertical strength and fallen fragility, the photograph captures a moment of becoming, when the heart is no longer able to pretend that loyalty lasts forever.

The Forsaken Toy lingers as a portrait of detachment and survival. It records the instant when companionship, whether real or imagined, is no longer enough to hold the weight of absence. Adwoa becomes both mourner and conqueror, standing tall above the fallen toy, carrying in her silence the story of every absence she has known. The photograph does not dramatize the loss, it simply shows it, letting the viewer feel the cold truth that abandonment is not always loud. Sometimes it looks like a child in a white dress, standing alone while her only companion lies forgotten at her feet.

The Float

The photograph captures a body suspended, only the legs visible, pale against the darkness that fills the room. The toes curl slightly inward, the ankles pressed close together, the posture held as though caught between motion and stillness. The floor below is wrapped in shadow, yet the shadow of the legs stretches forward, sharp and certain, echoing the form above. It is an image balanced between life and absence, a moment that refuses to resolve itself.

Beneath the floating feet, a small table holds an assortment of objects. Bottles and vessels that belong to a kitchen or living space are scattered across it. They are ordinary things, yet here they take on an unfamiliar weight. Their grounded stillness only deepens the strangeness of the body above them. The world of the everyday and the world of the uncanny exist side by side, and the distance between them is only a few inches of air.

The light isolates the legs, brightening them against the blackness until they become the only form the eye can hold. The rest of the body is absent, either cropped away or withdrawn into shadow. The silence of the image forces the viewer to imagine what cannot be seen. Are these legs in mid-jump, caught for a brief second before returning to the ground, or are they held in suspension by something more final? The photograph does not answer. It leaves the question open, and in that uncertainty lies its power.

The stillness feels too long to be a leap, yet too brief to be death. It is a moment stretched beyond its natural measure, balanced in a place where time falters. The shadow on the ground becomes as alive as the body above, a quiet double that waits with patience. The viewer is left not with clarity but with unease, drawn toward the possibility of despair without being given proof.

The Float unsettles because it does not declare itself. It lingers in ambiguity, pressing against the edges of what the image can reveal. It is the pause between two truths, a body that hovers between falling back into the world and vanishing from it.